In the wake of elections, I can’t help but wonder… has our nation really evolved since the ‘60s and ‘70s?

My relationship to the Kenyan government is an odd one. I was born here but spent most of my childhood in Sudan. I moved to Kenya when I was 15, and it was a culture shock. There were so many freedoms— people openly criticised the government, which was unthinkable in Khartoum. In Kenya, you could pretty much wear what you wanted and drinking wasn’t only allowed, it’s a cultural staple.

Now I’ve spent almost a decade in Nairobi.

With a few more years under my belt, I’m a little more jaded, have a little more knee pain, and my initial assessment of this country has evolved. When compared to Uganda or Ethiopia there are certainly more freedoms, at least visibly, but how represented by the government do people actually feel? And how far has Kenya come in the almost 60 years it’s been an independent nation?

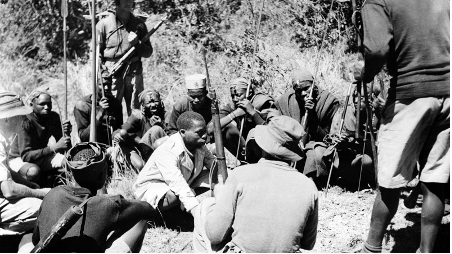

To get a better idea on the evolution of Kenyan democracy over the years I went back to the ‘70s. It wasn’t all disco fever, bell bottoms, and afros. After enduring the brutalities of colonialism for decades Kenya finally got its independence in 1963 and the slow, gruelling march to democracy began.

While we all know about the Mau Mau and the actual fight for independence, what we don’t always talk about are the after effects of colonisation. Who knew one tiny island could do so much damage? Just look at Africa on a map. It looks like the colonisers were like, “well I want Lake Victoria, you can have Kilimanjaro, let’s draw a line here finders keepers.”

What used to be open land was squished into one country, and like they’ve done in Palestine and throughout most of the global south, Britain did all they could to encourage segregation and conflict between groups, catalysing tribalism, classism, and many issues that are still embedded into our culture today.

With those issues and independence in hand,

our forefathers had to figure out who we were

as a nation.

Though it was a pivotal time in our history, there’s not a lot of documentation about the ‘70s. So I turned to someone who was here at the time: my mum.

“There was a lot of hope after the British, not just in Kenya but in Africa in general,” she tells me. “But even after they left, you knew your place. You had the white neighbourhoods, the Indian neighbourhoods…and we weren’t welcome in those spaces. We had our own government, but no one actually knew what that meant.”

It was a transitional time in Kenya and abroad. The Civil Rights Movement was taking off in America and amongst diaspora communities elsewhere. A mark of the ‘70s was the struggle between freedom and state control.

Fast forward to the ‘90s and we now have a semi-functional democracy. We saw the legalisation of political parties, restoration of anonymous ballots, and a two-term limit for the presidency. After decades of brutal suppression from Britain and then a revolving door of dressed up dictatorships, people finally seemed like they had a say in their government.

I was born in 1994, so to get a better idea of what our country looked like sociopolitically at the time, I sat down with 45-year-old JT, who voted in the ‘92 elections.

“When I was growing up people weren’t informed, there was no internet, and the radio and TV were government controlled in the 90’s,” he explained. “You could vote, which was huge for us, but you couldn’t speak out in favour of the opposition without fear. Now you can say whatever you want, and nothing will happen to you, the democratic space is much more free than it was”, he said.

I don’t disagree— people are very vocal about the government here. From living in countries where you wouldn’t dare voice your political opinion out loud, much less in writing, Kenyan Twitter really drags these politicians. And I’m 100% here for it.

The push for democracy though was very much influenced by Western donors, who were afraid of the effect political instability would have on their profits. Even in the ‘90s, outside pressure from Western countries still influenced an independent Kenya. When I talked to 23-year-old writer Irene about her feelings on the government, she expressed how the trickle down effect of those structures still has a hold on today.

“We’re not that different from America honestly. This government of ours only cares about money, with how much money goes “missing” it’s not about the betterment of everyone, just the profit of the individual”.

She’s not wrong.

For all the government’s lofty ideals on the environment, in 2019 American exporters shipped more than 1 billion pounds of plastic waste to 96 countries including Kenya. Most of it ends up in our rivers and oceans. Between its own people and the financial gain, the Kenyan government will always choose the latter. And with that mentality, there is no ethical obligation.

While this doesn’t seem like an immediate threat to democracy, it does raise a question: when the will of the people contradicts the government’s bottom line, what do you think they’ll choose?

It’s not just a question for our government. We need to look at our history, specifically how capitalism has evolved from colonialism and who it benefits, to unpack the problem. Profit seems to have taken the place of the old empire, and only complicates questions on identity.

Irene comes from a mixed family— with one Luo parent and one Kikuyu parent, so this topic is a sensitive one, and leaves a lot of people feeling like they’re not sure where they fit in the political landscape and even within their own families.

“Every election is so stressful because there’s nowhere to go,” she shares. “I can’t go to shags, so we just stay in Nairobi and hope for the best.”

Tribe always comes up in politics, but has this always been the case? If we talk about tribes as an ethnic group with a common language, then sure. But tribe as an administrative entity defining participation in state government is a colonial-era construct that still dictates how many Kenyans view the government and our nation at large.

During the ‘70s, affiliation with your tribe was the one tie you had to a past. Those ties were reinforced by British rule, and budding democracy and country identity required unlearning those divides. But it was not an easy task— unlearning takes time.

For our parents and our grandparents, the right to vote was revolutionary.

As Nancy Mwai, who was a teen in the ‘70s, tells me, the fact that we may have a female VP is revolutionary, and a marker of how far Kenya has come.

“It gives me hope,” she tells me.

In contrast, a lot of young people are choosing not to take part in these elections, not because they’re apathetic, but because they don’t feel heard by the government. A lot of my peers feel that way.

When you don’t feel heard, it’s difficult to take part in this lumbering political machine and trust that they have your best interests in mind. It’s not all doom and gloom though, people are finding ways to create change in their communities, just on a more grassroots level.

“It’s not that we don’t care, it’s just that we don’t feel included. Especially when you’re queer, or from a mixed family, or just a young person in general because girl, we struggling out here—we’re finding ways to make a difference in our own little groups. Not through tribe but through shared interests and values”, Irene remarks.

We have a voice that our parents and grandparents didn’t have, but if the government wants young people to be more engaged, they have to stop treating us like our only worth is our numbers. Because young people are not apathetic about Kenya, they’re just not interested in upholding the same oppressive structures our parents and grandparents struggled under. We want to see big changes in the institutions this country was built on, so that Kenya actually represents its people.